The majority of the 56 victims of the blood disorder cluster at Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. were vocational high school graduates from poor families in small cities. They went to work at Samsung in the late 1990s when South Korea boasted one of the world’s highest college enrollment rates, 61 percent. Before the victims fell to a variety of blood disorders, Samsung, which was on its way to become the world’s largest chipmaker, was their source of pride and opportunity. On July 9, Hankyoreh 21, one the county’s few independent weeklies, profiled four victims from the small city of Kunsan in a cover story. The following is a translation of the report [All brackets are added]:

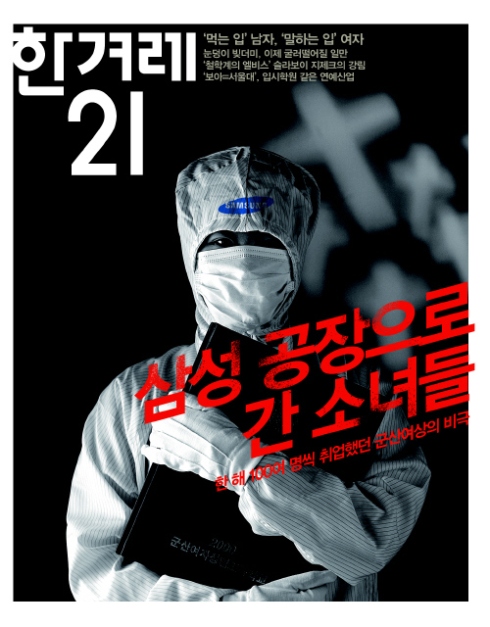

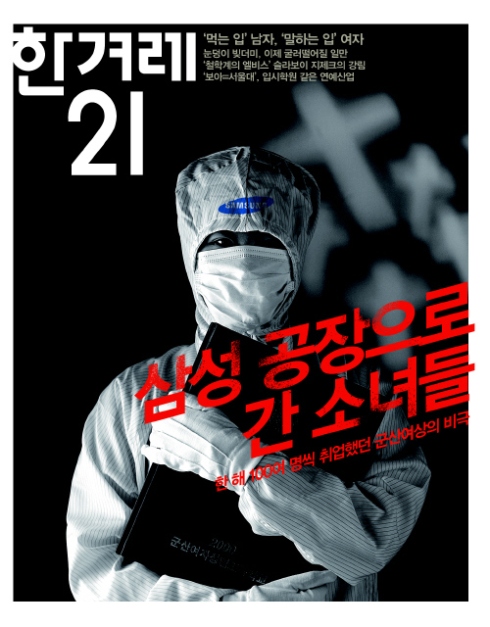

The July 9, 2012 issue of Hankyoreh 21

Sitting quietly on the edge of Kum River, the southwestern city of Kunsan was a bustling port city under Japanese colonial rule of 1910-45 when it was a conduit for the Japanese to siphon rice off the Korean peninsula. The colonial master called the city Kunsan of rice. In the 1960s-80s, largely left out of South Korea’s fervent industrialization, Kunsan’s wealth declined. For young girls living in a city whose skyline is still dominated by colonial edifices and floating piers, working at Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., was a giant leap forward.

The four former Samsung Electronics employees, Yun Seul –ki and Yi Ah-young, both 31 years old; Kim Mi-seon, 32 years old; and Chung Ae-jeong, 35 years old, went to the same Kunsan high school. Yun and Yi are class 2000. Kim is class 1998 and Chung class 1996. They all spent least a year together with one or two of the other girls at Gunsan Girls Commercial High School, perhaps singing together the refrain of their school anthem: “My proud Gunsan Girls Commercial High.” About a decade later, Yun died. Yi is suffering the aftereffects of surgery. Kim is on her sickbed. Chung lost her husband to a disease he contracted while employed at Samsung. Their medical conditions are: severe aplastic anemia; intermediate tumors in the head and neck; multiple sclerosis; and leukemia. It is unlikely that other Gunsan graduates share the bitter fate. Each contracted the disease while working at the Samsung LCD plant in Chonan or the semiconductor lab, and the LCD plant in Kiheung.

Over the gate of Gunsan Girls Commercial, a banner flies to congratulate recent graduates on their first jobs. Six are employed as operators at a Samsung Mobile Display plant in Chonan. About thirty have jobs at other semiconductor makers.

Even before graduation, the girls left home to partake in production of semiconductors, locally dubbed “the rice of industry.” In the cleanroom, no speck of dust was allowed. They stripped off their school uniforms and slipped into dirt-free garments covering themselves from head to toe. They covered their long or short hair, and their brown eyes were exposed, still sparkling. The rice of industry began to engulf the young girls from a small and old vocational school.

Yi began work at Samsung in June 1996, about a month later than Yun. Yi still vividly remembers the day she entered the company fifteen years ago. For a vocational school girl of a small city, working at the world’s biggest electronics maker was the source of pride. Without standout academic credentials, one could not land a job at Samsung. A year prior to her employment, Only 40 out of 100 applicants from her school received employment offers.

Samsung sent interviewers to the school. Three interviewers interviewed about seven applicants together. “Semiconductor jobs were popular because they paid well, and had good dormitories. I wanted a Samsung job because I wanted to make a lot of money,” said Yi. A month later, she got on board the bus sent by Samsung for its in-house training facility. Only five of her 47-student homeroom class landed Samsung jobs. .

Yi was posted as operator to the chemical vapor deposition process, in which she used chemical gas to add dopants to a pure semiconductor to modify its electrical properties. Working on a three-daily shift was not easy to manage. She had skin rashes and even collapsed. “My health got worse very much. I found it hard to get adjusted to the company,” said Yi. She resigned as operator in April 2002. The following year, she went to college.

She often became sick for no particular reason. She felt exhausted, as if falling victim to a severe flu. “Once I got sick, it lasted a month,” Yi said. During four months a year in those years, she felt feeble. She thought it was a tough flu to beat. She took medicines and saw a doctor. The illness continued to hound her even after college graduation.

It was the summer of 2009 when she began to see doctors at big hospitals in Seoul. They found intermediate tumor glands in her neck and head. One of her doctors described them as glands in her nervous system. “The condition is so rare that there are three patients with it a year,” Yi quoted her doctor as saying. Yi said, “I had the tumors removed quickly. I suffered facial paralysis.” The facial paralysis has become less severe, and she now works at a new job.

Yi believes she developed the tumors while employed at the semiconductor plant. “A senior colleague of mine, who was a line inspector, collapsed with a foaming mouth. Much later, I came to know that one predecessor had died of leukemia,” she said. “In 2000, when I was an operator, there was a blackout.” There were concerns about possible chemical leaks during the blackout. Yi has considered filing a request for workers’ compensation, but she did not file it. “They don’t recognize even the dead ones. Why would they grant my request? I feel fortunate that I got out of there [Samsung] alive.”

Yi had not been in contact with Yun since graduation. She came to know of the death of Yun, when interviewed by Hankyoreh 21. “We were dying to work at Samsung. I didn’t know all ended this way

Yun is the 56th victim of blood disorder clustering in the semiconductor industry as profiled by SHARPS. She died at a Seoul hospital on June 2. “I will live in Japan.” This Yun often said to her mother. A Kunsan native, Yun wanted to go to college in Japan. She thought herself Japanese. Yun was a fan of SMAP, a Japanese teenage pop band. Thirteen years of struggling with severe aplastic anemia has deterred her dream.

Yun wanted to go to a prep school to improve her chances for college. However, at the request of her mother, Shin, she went to Gunsan Girls Commercial, a high school whose graduates often land good industry jobs.

In May 1999, ahead of graduation, Yun applied for a position at Samsung. A month later, she began to work at the LCD plant in Chonan. Shin was proud of her daughter for working at a big corporation. Yun was responsible for cutting chemically glazed LCD panels into size. When Shin asked Yun about her job, she always indifferently said, “I am just a factory girl.” The mother said, “I did not expect her to work on a blue-collar job at Samsung when she was employed at the company.”

Five months into the job, Yun fell on the factory floor. She thought it was a flu, the one that got worse. She did not get better. Yun was diagnosed with severe aplastic anemia, a condition where bone marrow does not produce sufficient new cells to replenish blood cells. Yun, herself a regular blood donor since high school, was an unlikely victim of the disease. Her long fight against it began. In 2002, she could nevertheless begin to study Japanese at a local college.

Her condition grew worse. She stayed home longer, passing time by reading Murakami and other Japanese fiction. Learning news that a former Samsung employee would receive workers compensation for aplastic anemia, she decided to file the request. But her time ran out. She died in May.

Kim is two years senior to Yi and Yun. In 1997, she began to work as an operator in another LCD plant of Samsung. She went through what the other two experienced two years sooner. It was March 2000 when she became sick, about six months apart from Yun. Kim is under treatment in Seoul for multiple sclerosis and optic neuritis. Multiple sclerosis, the cause of which is yet unknown, can be caused by exposure to hazardous chemicals and excessive stress. It damages the myelin sheath, which in turn slows down or blocks messages between the brain and body. Kim is visually impaired because of the optic neuritis.

“They paid me 10, 000 won (US$10) in stipends after the interview. I was so happy,” Kim said. About 100 girls from her class went to work at Samsung’s LCD plants. “It was during the 1997 financial meltdown [in the country]. There were fewer jobs going around. I was glad to get selected by a big corporation with good pay,” she added. She was hired in June 1996 and deployed to a soldering job after months of training. “At first, I was responsible for soldering taps on LCD panels after cleaning them. After a year, I was responsible for lead soldering,” she said.

After three years into employment, she became paralyzed on the left side of her body. She could not lift the left arm anymore. There is no history in her family of any such condition.

In March 2000, she took medical leave. Her condition worsening, Kim eventually resigned from the company. “Mother wanted me to seek workers’ compensation. I opposed it.” She said. “I believed I could get back to work. The company said my workers compensation request would not likely be accepted because the illness was caused for personal reasons.”

She went in and out of hospital as the condition of sclerosis fluctuated. She lost vision in the right eye. With her left eye, she can barely read large fonts on the computer screen. Last year, Kim filed a request for workers compensation with the help of SHARPS, which she came to know through news reports. “I did lead soldering, and air purifiers were often non-functional. I sometimes wore only a paper mask. We did not know how hazardous our jobs were,” she added. She still collects prescriptions every two months. She regularly has to undergo antibody and blood tests. “I would have not worked at a semiconductor factory should I have known it was such a place.”

The memory chip industry experienced a great boom in 1995. The release of Windows 95 boosted prices of memory chips. Chung, a mother of two, is now a preschool teacher in the city of Siheung. A Gunsan Girls Commercial graduate, she is a victim of the occupational disease cluster at Samsung. She lost her husband, himself an employee of the company, to leukemia.

Chung followed in the footsteps of her sister, who went to work at Samsung after graduation of the same high school. “If you did not find a white-collar job in Kunsan, then Samsung is the next on your list,” she said. In October 1995, Chung was employed as an operator at the plant in Kiheung. Many of the young girls feared leaving home to work elsewhere. Samsung’s well-appointed dormitories eased the fears. “They even considered our conduct records. They preferred upstanding students without truancy and cutting records.” Chung said. About 150 graduates including her landed jobs at Samsung.

Three years into Samsung, she met Hwang Min-woong, an engineer, during a company choir practice. They got married. In 2004, Hwang was taken to the ER for flulike symptoms. .He was diagnosed with leukemia. Nine months later, he died while awaiting marrow donations. It was ten days after Chung gave birth to their second child. The company said the disease had nothing to do with Samsung. She has continued to work at Samsung. Chung’s story is depicted in A Clean Room. She helps former Samsung employees to file requests for workers compensation,

On June 27, 2012 afternoon, girls began to pour from the gate of Gunsan Girls Commercial, bursting laughs as any teenager girls would. Over the gate, a banner flies to congratulate recent graduates on their first jobs. Six are employed as operators at a Samsung Mobile Display plant in Chonan. About thirty have jobs at other semiconductor makers. When asked what they know about working conditions at Samsung, some students answered, “We’ve been talking about it. It’s dangerous to work there, but Samsung is still Samsung. They pay well.”

“Samsung used to employ graduates in busloads,” one girl said. “There are not many openings at Samsung. They don’t have money either.” Another concluded, “We came to a commercial high school because we want jobs after graduation. There are not many jobs going around in Kunsan.”

“There are few well-paying jobs in Kunsan,” school sources said. “The students tend to favor the operator positions.” Lee, the former homeroom teacher of Yun and Yi, said, “In 1999, after the financial crisis, when jobs were scarce, we found Samsung’s mass hiring encouraging.”

“We did not have any awareness or information about the danger of semiconductor and LCD production,” said assistant superintendent Park. “It is very deplorable to see my students suffering.”

Leukemia and other cancers don’t require working at Samsung Electronics. However, it is unusual for a disease to cluster at the same production line of the same plant in the same period. The working conditions ten years ago at the production line that no longer exists is the point of contention between Samsung and former employees over whether to determine their medical conditions are occupational diseases. Samsung and the government focus on the now-disintegrated production line, while the victims point to the decrepit machines used on the line.

“We deplore the death of Yun, a former colleague of ours,” said a Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. spokesperson. However, he categorically denied any relationship between her disease and her job. “Yun worked for just six months, including four months of apprenticeship. She was responsible for mechanical operations, which did not require chemical processing. Pre-employment health screening was not thorough enough to detect the symptoms of her condition,” the spokesperson said. Countering Samsung, Yi Jong-ran, labor attorney with SHARPS, said: “Chemicals could have entered the air when Yun cut LCD panels. Aplastic anemia has a short incubation phase and be caused by a short exposure to [hazardous materials].”

Concerning Yi and Kim, the Samsung spokesperson said, “The occurrences of the diseases should be measured against the number of graduates. It does not appear scientific when you combine two different diseases to create causality because the two former employees went to the same school.” Asked to measure the occurrences in a particular place, during a particular process and in a particular period, he answered that it made little sense.

Samsung proposed a public examination. “SHARPS disclosed 137 workers whom it says have come out. Their identities are not disclosed, and they came down to a disease at differing points of time. If who they are, what diseases to which they came down and what line of production they were are disclosed, we can examine their cases together,” said the spokesperson. Says attorney Lee, “The Samsung Health Research Institute [a health research arm of Samsung Electronics] has proposed dialogue. However, Samsung used money to stop the workers from requesting workers compensation and to drop lawsuits. They did not do anything to build trust. What dialogue is possible, given the situation?”

On June 14, Samsung Chairman Lee Kun-hee paid respects at the mortuary of four Samsung C&T employees who were killed in a helicopter crash in Peru. He told the conglomerate to revamp safety measures for Samsung employees working overseas. There are fifty-six mortuaries the tycoon passed by. A lack of dirt, all white, is not necessarily clean. The girls’ dirt-free suits were dreadfully white.

Read Full Post »